[ad_1]

Unearthing Natural Pigments in the CMA’s Collection

By Katie Rovito, third Year Graduate Intern in Paintings Conservation, and Elena Mars, Samuel H. Kress Fellow in Objects Conservation at the CMA

Throughout history, artists have used earth’s natural resources to create works of art. These can come from a variety of sources including rocks, minerals, clays, and even plant-based materials. Linseed oil, a common binder used in Western paintings, is made from flax seeds; dyes used to create vibrant textile colors come from plants; and charcoal, a common drawing material, is just burnt wood. To celebrate Earth Day today, we are reflecting on paintings and objects within the CMA collection that highlight artists’ use of earth pigments.

From the earliest cave paintings to modern art, artists have been making pigments from rocks and soil. The term “earth pigments” refers to those mainly composed of silicates, clays, iron oxides and hydroxides — all abundant minerals in the earth’s crust. The color of the paint depends on the ratio of these minerals. If you’ve ever driven out west and seen the red and yellow landscape, then you’re familiar with earth pigments.

Traditionally, the rocks were washed and then ground with a mortar and pestle to produce a fine powder. The pigment was refined further by levigation, a technique that separates the particles by size. The pigment could then be mixed into a paint with the desired binder or medium, such as linseed oil, egg, or plant resin. Special tools, such as the glass muller shown here, help break up larger particles of pigment and disperse the pigment evenly in the medium.

What are some common types of earth pigments?

Iron earth pigments are ubiquitous and can be found throughout the museum in paintings, objects, drawings, and textiles. Ochers range from yellow to red depending on if they have more of the yellow mineral, goethite (iron hydroxide) or the red mineral, hematite (iron oxide). Siennas come from the yellow goethite-rich minerals but different from ochers because they also contain a small amount of manganese oxides. If you’ve ever painted with raw sienna, you’ll notice it’s more transparent and a little warmer than yellow ocher. When raw sienna is heated, the iron hydroxide reacts to form the red iron oxide, giving us the pigment “burnt sienna.” Umbers are brown pigments that get their color from its much higher percentage of manganese oxide.

Green earths or “terre verte” get their color from the iron-containing green clay minerals glauconite and celadonite. Have you ever wondered why some of the faces in the medieval gallery look green? Medieval painters often used a mixture of green earth and lead white to paint the undertones of flesh. This was referred to as a “verdaccio” layer. They would then finish painting the skin tones on top, often using organic red pigments that are known to fade when exposed to light. When the fugitive pigments fade, we see the green earth underpainting, as in the Coronation of the Virgin.

Conservators use a variety of techniques to identify earth pigments. One of the most common methods is X-ray fluorescence (XRF), which identifies the chemical elements present in a particular spot on a painting. High concentrations of iron in reds, browns, or yellows suggest the use of earth pigments. When manganese is identified in addition to iron, this can indicate that an umber or sienna was used.

When conservators analyzed Caravaggio’s Crucifixion of Saint Andrew with XRF during a 2016 treatment, they identified iron and manganese throughout the painting. There are umbers in the dark background and red ocher in the lower right figure’s garment. The flesh tones were painted with mixtures of lead white and iron earths, and yellow ocher and lead tin yellow were identified in the yellow paints.

Another type of earth pigment, Maya blue, was made with a combination of indigo and natural clays. This pigment was created by the ancient Maya civilization between AD 250–900. It is made by mixing the indigo extract of añil plants (Indigofera suffruticosa) with palygorskite and or sepiolite clay and heating the mixture. Through this process the indigo bonds within the clay matrix, producing an extremely stable pigment that is even resistant to acid. In some cases, traces of the pigment still survive on artworks. We are currently studying the remaining pigment on these earthenware ceramic incensarios, or incense burner supports, to determine if Maya blue is present.

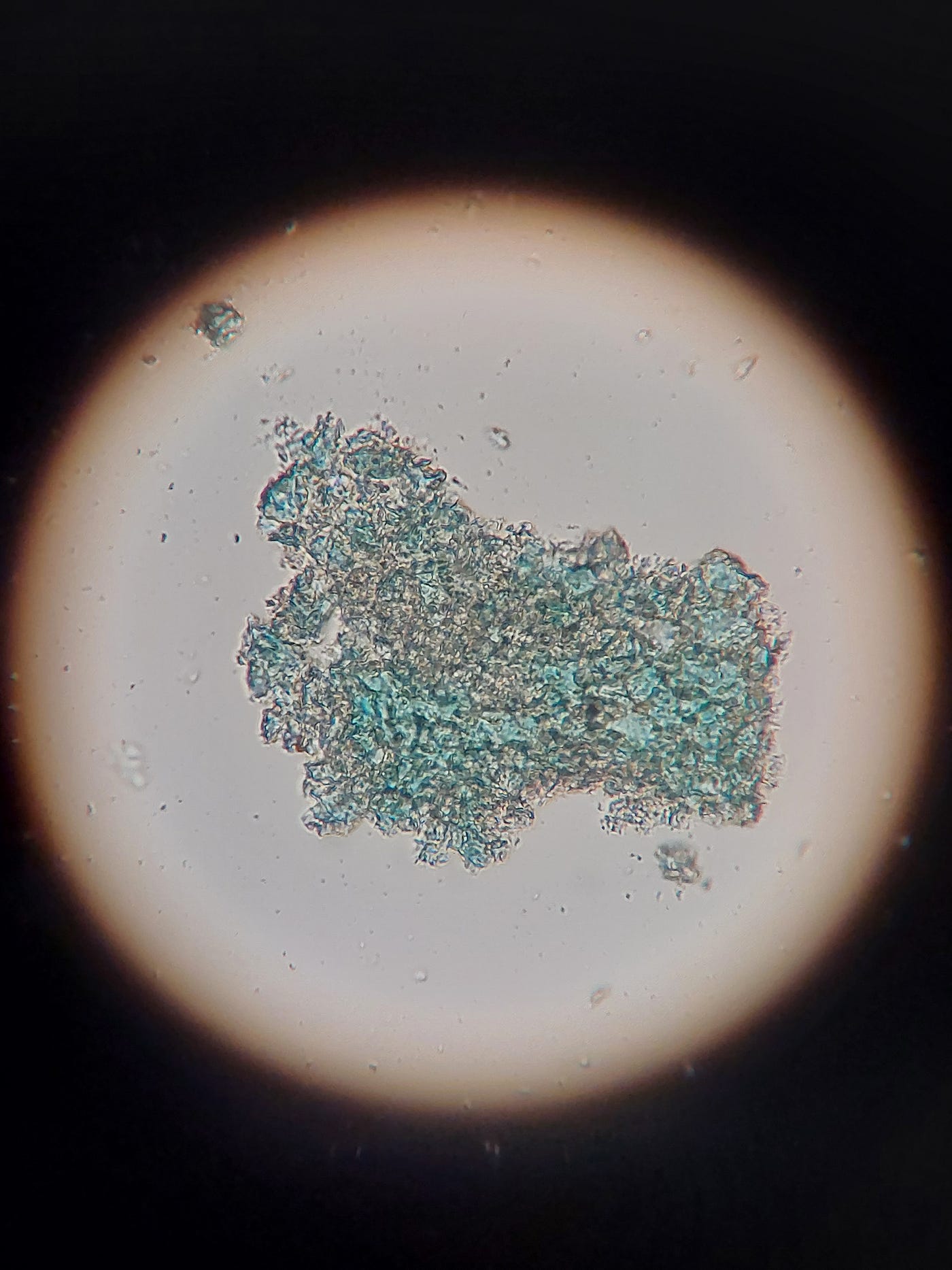

The remaining blue paint on the incensario seen below is light blue in tone and still quite vivid. Studies on Maya blue pigment indicate the color can range in tone from gray-blue to bright turquoise.

The blue pigment was resistant to concentrated nitric acid, and we identified palygorskite, both of which suggest it is most likely Maya blue. XRF analysis of this pigment did not identify any of the elements usually found in blue mineral pigments, like cobalt, manganese, and copper. This rules out common blue pigments like azurite (copper carbonate) or smalt (cobalt glass). Additionally, under the microscope the pigment is transparent turquoise and is clustered with plate-like particles, which also indicate Maya blue.

The CMA collection is full of examples of artists using materials from the earth to create works of art. Check out the indigo in Untitled Noren Partition (23) on view in gallery 229C or the burnt umber in Study for “The Bear Hunt” (for the Alcázar, Madrid) on view in gallery 213. Natural materials abound in the Andean, Mesoamerican, and Intermediate Region galleries 232 and 233.

Also, be sure to visit the exhibition Cycles of Life: The Four Seasons Tapestries to see beautiful textiles all colored with natural-based dyes and to learn more about conservation treatment of the works. In celebration of Earth Day, look for these materials and artworks during your next visit.

Additional Resources

To learn more about pigments and how they are identified in art works, check out the Colour Lex website which has multiple case studies and tools for identifying pigments: https://colourlex.com/

And check out this Natural Pigments’ article about earth pigments from Italy to learn more about where earth pigments come from and how they’re made into paint: https://www.naturalpigments.com/artist-materials/cat/natural-pigments-supplies/post/italian-earth-pigments/

[ad_2]

Source link

:strip_icc()/BHG_PTSN19720-33d9cd22f6ab49e6a21982e451321898.jpg)

More Stories

BSA Film Friday: 11.25.22 | Brooklyn Street Art

FEATURES – Art in VR with Casey Koyczan

Julie Karpodini: Painting Instinct – Jackson’s Art Blog