[ad_1]

Discover our curator’s top exhibitions to visit in London during May.

By Phin Jennings | 05 May 2022

Last month, The Venice Biennale’s International Art Exhibition opened to the public. This year’s title, The Milk of Dreams, is taken from a children’s book by artist Leonara Carrington. It is set in a fantastical world where everyone and everything is in a state of constant flux: identities are not fixed and characters constantly re-imagine themselves and their surroundings. The Biennale’s curator Cecilia Alemani describes her exhibition as an “imaginary journey through metamorphoses of the body and definitions of the human”. For those of us in London – decidedly less enchanted than Venice – I hope that these three exhibitions that explore folk tales and fantasy might bring something of the sense of wonder at this year’s Biennale.

6 – 25 MAY

Once Upon a Time… at Flora Fairbairn (image courtesy of the gallery)

This exhibition’s press release describes folklore, myths and fairytales as examining the light and the dark in human nature. The number (55, if you were wondering) and variety of artists on show illustrates how well this description also applies to visual art. Drawings, paintings and sculptures all have the ability to communicate truths and feelings about the world in fantastically veiled ways. Like stories, the works in this exhibition employ invented characters and invented scenarios to consider very real subjects.

Two of the artists who I think do this best are Suzanne Treister and Paula Rego. Treister’s works feel like parodies of corporate presentations about emerging technologies. They feature painted or drawn networks of brightly coloured nodes displaying lofty but seemingly unconnected words and phrases: “SHAMANIC ALGORITHM”, “LUMINOUS DATA TRANSFER”, “CARL JUNG”, “KABBALAH”. The words are sensational, but lose their resonance when displayed in this saturated and nonsensical configuration. To me, Treister’s text-based science fiction world better represents the politicians and businesspeople who hold power in the real world than most purportedly non-fiction accounts.

Rego, whose work is also on show as part of this year’s Biennale, uses fiction to address political realities in a similar way. In her cartoon-like figurative works, she employs a cast of characters including anthropomorphised spiders, angels and dapperly-dressed frogs to obliquely reference abuses of power and violence towards women.

4 – 28 MAY

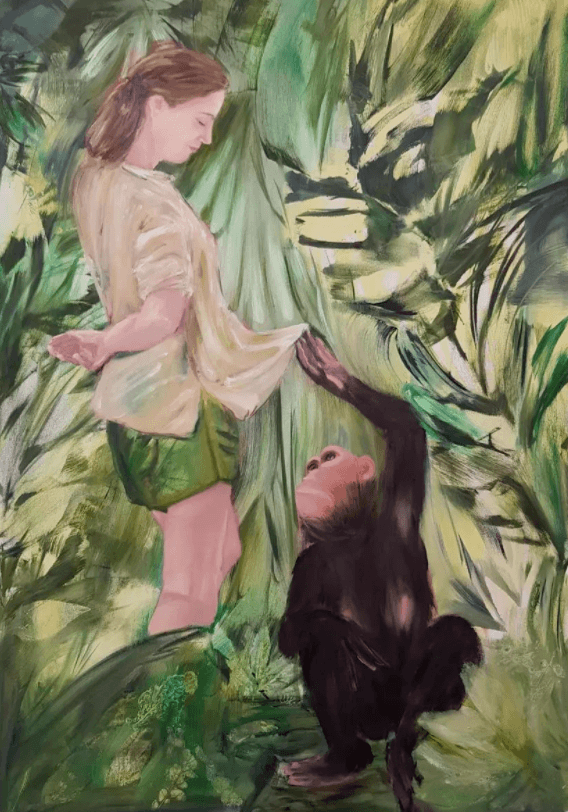

We Think Back Through Our Mothers by Amy Steel (courtesy of the artist)

Frogs also abound at We Are The Ones Who Know, Amy Steel’s solo exhibition at Soho Revue, organised in collaboration with Purslane. Last May I wrote about Steel’s exhibition at Niru Ratnam, where I was impressed by the painterly abstraction in her work: her paintings’ celebration of the “simple but endlessly generative relationship between paint and canvas”. A year later, although the paintings are still just as beautiful in their form, I am more interested in their content.

“What if our relationship to animals was one where we accepted our likeness and didn’t assume a position of authority?” We are told in the gallery text that the artist often returns to this question, which goes some way to explain the human features worn by many of Steel’s animal subjects, like the frog with breasts in Rose. In fact, breasts are everywhere in this show, more often disembodied – floating in a lake or ocean – than attached to bodies. This serves to remove them from our sad, voyeuristic, woman-shaming reality and recast them as an equal and beautiful part of the artist’s innocent fairytale world.

What can this world teach us about our own? Perhaps it shows us how much better off we would be if our relationship with animals (and with other humans) was more defined by likeness than authority. Because I Know So Little I Grope For More – a large painting which features a troop of monkeys, shoulder-deep in a mountain lake, reaching blindly for floating breasts – inspires equal feelings of amusement, curiosity and wonder at the natural world and the female body. Here, there is no hierarchy, no “natural order” and no shame.

26 APR – 1 JUN

Installation view of Hans Josephsohn at Galerie Max Hetzler

It might require some mental gymnastics to argue that this exhibition references fantasy and folklore in the same way that those we have already seen do, but something about Hans Josephsohn’s rough sculptural renderings of the human form makes them feel like fairytale characters. Perhaps it is the fact that – although they are cast in brass in the artist’s Swiss studio – their dull tones and lumpy forms remind me of the English landscape that is the subject of so much folklore. On a plinth in the centre of one of the gallery’s rooms stands an Untitled work: a 140cm tall lump of brass cast from a clay mould with a just-about-decipherable face. It reminds me of stories about Finn McCool, a legendary Irish giant who was known to lose his temper and throw giant clods of clay – one of which ended up becoming the Isle of Man.

We see the same stories and characters crop up in folktales from all over the world, although they were conceived of independently during a time long before globalisation. Many people think that these archetypes are evidence of folklore’s ability to communicate basic truths about being human. This is a huge – perhaps impossible – job, which I often see wrongly attributed to figurative artists as an attempt to make their work seem more profound than it is. I don’t think a lot of artists are interested in looking for universal truths, and that’s okay. But, seeing Josephsohn’s work and hearing the way he speaks about it, I can see parallels with the universality of folklore. His reference points include mediaeval art, Romanesque churches and Indian temple reliefs, as though he is trying to capture a transhistorical human essence that they all share. As he puts it, “sculptors across history were my true relatives”. Drawing from such a historically and geographically diverse range of sources, the artist finds archetypal representations of the human form and therein, in the words of this exhibition’s text, “finds a neutral plane in which the body is stripped bare.”

[ad_2]

Source link

:strip_icc()/BHG_PTSN19720-33d9cd22f6ab49e6a21982e451321898.jpg)

More Stories

Gurney Journey: USA Today Recommends Dinotopia

“From Generation to Generation…” — A Sanctified Art

The Public Theater’s Under The Radar Festival Lights Up NYC This January