When SFMOMA established its archives in 2006, the museum was lucky enough to have its early records, dating back to its founding in 1935, still intact and ready to be accessed by the research public. Among those records were ones documenting the activities of the Women’s Board, formed in 1934 as an auxiliary to the almost exclusively male Board of Trustees and tasked with fundraising, event, and publicity responsibilities.

“When it was set up it was meant to be primarily social, with the idea of a Lady Bountiful, you know, to receive at receptions and previews and so on,” SFMOMA’s first director, Grace McCann Morley, explained in a 1960 interview with the Regional Oral History Office. “Well, these women were of a caliber to whom that would not have had continuous appeal. They were perfectly willing to do their duty socially, and it was very necessary and helpful, of course, to have that kind of social representation at our big openings and previews and so on, and the social publicity that it produced was very good. But they were of a type to respond with more conviction to other more serious interests, and that’s why I called on them so continuously and so urgently, and very often at much sacrifice of their time, energy and even money, to give me support in the educational development of the museum.”

Morley, seated far right, in a meeting with the members of the Women’s Board, c. 1956

It may be easy, as I once did, to dismiss at first glance the volunteer work of well-to-do women, but it would be a mistake. These individuals established the foundation of SFMOMA as we know it today. From early on, their focus, with the guidance of Morley, was squarely on education and community outreach. The museum’s film program and other important offerings such as tours, classes, lectures, concerts, and performances were established within the first couple of years of the group’s operations.

Here are just a few of the events sponsored by the Women’s Board:

Filmmaker Frank Stauffacher’s Art in Cinema film series

Koto performance by Shinishi Yuize, 1953

Ravi Shankar performing on April 10th, 1957

School tour of the exhibition Design in Scandinavia, 1957

Children’s art class, 1961

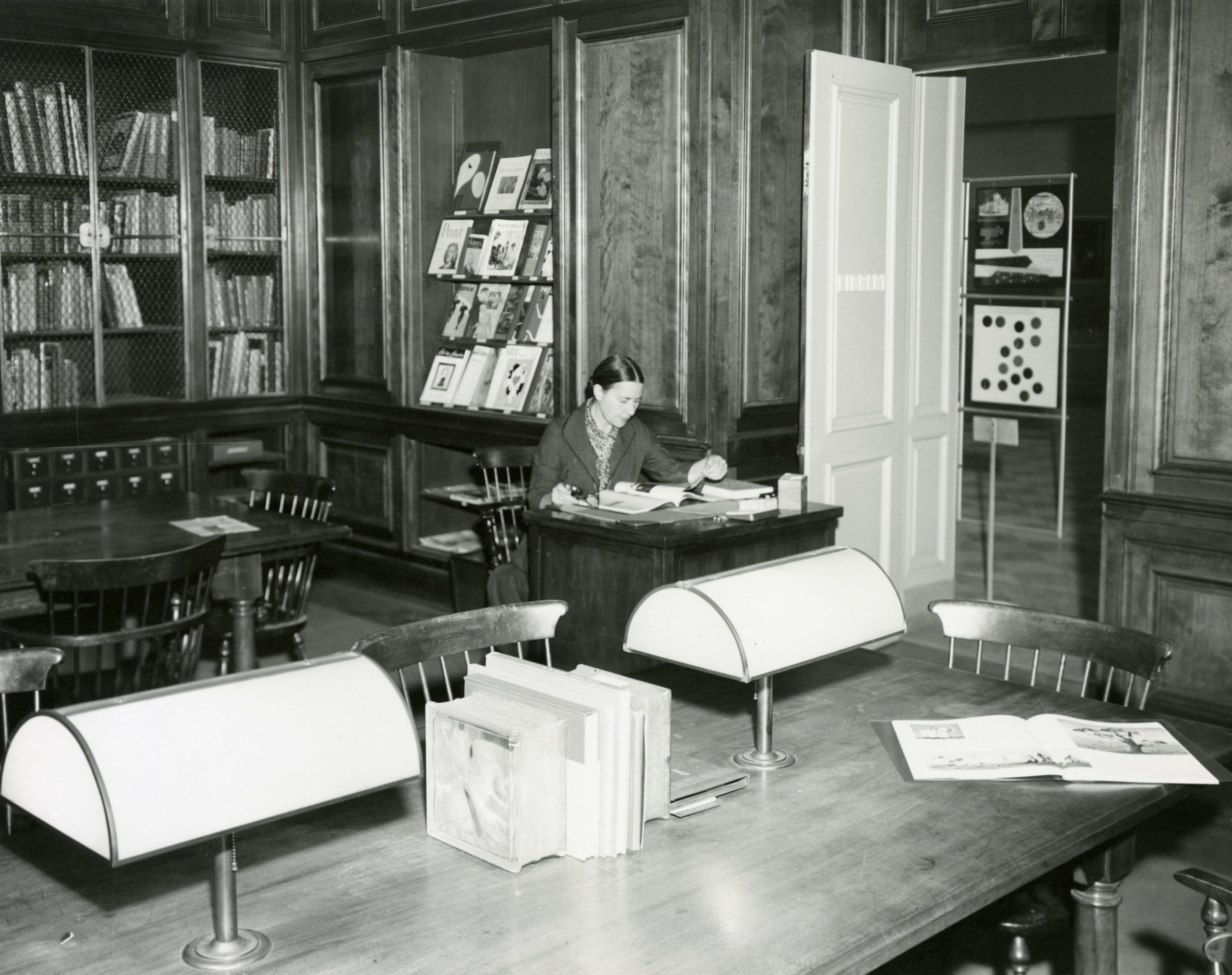

Before SFMOMA could afford a paid staff, the Women’s Board oversaw numerous endeavors at the institution. Member Louise Ackerman volunteered at Saturday morning children’s art classes, and managed the library from 1938 until the museum could afford to hire a librarian. Clara Heller paid for art periodical subscriptions for the library; she and Helen Crocker Russell also donated film equipment. The group established a $25 revolving fund to set up the museum bookshop, and upon the recommendation of Marge Lindner, the museum even opened a branch in the Parkmerced Towers in 1952. Its goal was to “enlist the interest and active participation of a great number of residents who could not otherwise take advantage of museum membership.” The space hosted classes and exhibitions.

Bookshop at the Van Ness building, 1953

Library at the Van Ness building, n.d.

Parkmerced gallery, 1952

Morley relied on the Women’s Board heavily during World War II, when the draft left the museum understaffed. Its participation in the Red Cross Arts and Skills Program was among its most notable activities during this period; member Dorothy Liebes, a textile designer, introduced the program to her colleagues in 1943.

Meeting minutes describe the Red Cross Arts and Skills Program as consisting of “artists from many fields who are willing to donate their time and services to teach their crafts to the convalescent soldiers, sailors, and marines now in the seven service hospitals in the Bay Region. This work will be carried on under the supervision of an American Red Cross field worker, its object being threefold: first, to provide the men with recreation; second, to teach them to re-educate their muscles; third, as a morale builder as well as a possible means of support.”

It was an effort to use art as therapy for wounded soldiers, recruiting local artists as teachers and placing them in military hospitals. A motion was passed that the work be carried on under Liebes’s chairmanship and that the museum help register artists willing to give their time.

Promotional brochure for the Red Cross Arts and Skills Program (recto).

Promotional brochure for the Red Cross Arts and Skills Program (verso).

Bay Area artists, including Ruth Armer, Victor Arnautoff, and Clay Spohn, volunteered for this program in many capacities — as instructors, as jurors for the exhibitions of the works produced, and as advisors. The artist and writer William Justema proposed expanding the program to include writing workshops. Writing to Marion Chidester, Justema explained that “there are many wounded men who have no feeling for the plastic expression who might, however, be helped by having their means to express themselves in writing increased. In my own case I was often sustained through the fourteen months I spent in the Army by a kind of verse diary I was always working on — in the sense that it gave me a thread for my days, a continuous interest… Everyone is said to have a story in him — the wounded surely have.”

Justema’s suggestion does not appear to have been incorporated into the Red Cross Arts and Skills Program. The body of records, though, reflects the commitment so many local artists had to this program.

Installation views of 2nd Annual West Coast Arts and Skills Exhibition, American Red Cross in 1948

Another significant Women’s Board contribution was the Rental Gallery, launched by Chidester in 1947. This precursor to the Artist Gallery at Fort Mason was an early museum effort at community outreach. Works were exhibited in the gallery space dedicated to the program and available for rent or sale to the museum public. “There is a section of the art-minded public which does not find the time to attend the many interesting exhibitions in the museum,” Chidester explained in a report. “But with the aid of the Rental Gallery works of art by local artists are circulating in private homes — in most cases the environment for which they were created. Some become a permanent possession through purchase. Thus this plan inevitably serves the artist.”

Rental Gallery invitation.

In its early decades, Rental Gallery exhibitions featured Bay Area artists such as Ruth Asawa, Elmer Bischoff, Richard Diebenkorn, Claire Falkenstein, Adaline Kent, Emmy Lou Packard, David Park, Nell Sinton, and Hassel Smith, to name a few.

Installation view of the exhibition Rental Gallery in Spring 1954

Installation view of the exhibition Rental Gallery in Spring 1955

Installation view of the exhibition Autumn Rental Gallery in 1956

In the 1956, the Women’s Board added a school program component to the Rental Gallery, extending the reach of its existing rental and educational activities. Schools were invited to participate by bringing their students to the museum. The children were given an introductory tour by a museum docent and then brought to the Rental Gallery, where they voted by ballot for their favorite work.

Installation view of the exhibition Spring Rental Gallery (1958) with school group in the background

Rental Gallery School Program brochure

Thank you letter from student

The Women’s Board contributed in myriad meaningful ways beyond their original mandate, often behind the scenes. Members sent care packages to enlisted staff during World War II, for example. And after the war, they donated art books to damaged German university libraries. Back home, Janette Spencer worked with engineering to oversee lighting in the galleries; Frances Elkins helped furnish the museum member’s room; Margery Smith managed the renovations to the staff break room and kitchen.

In a 1982 oral history with the Archives of American Art, Morley mentions that whereas the board met once a year at most, the Women’s Board “met monthly and had a very deep interest in everything that went on in the museum, lending a lively support to everything it did. This was a constant encouragement and solace in periods of disappointment and in failures to achieve the standards that one aspired to.”

The board disbanded in 1975 and joined with another auxiliary group, the Membership Activities Board, to form the Modern Art Council (MAC). On the occasion of this merger, Mary Heath Keesling, former trustee and President of the Women’s Board, summarized, “To attempt to write about the spirit of the Women’s Board is like trying to describe in everyday terms one of the nature’s rare phenomena. The spirit, which was a unique quality of this particular board, was based on belief, and this belief created a force — a selfless and tireless dedication that has prevailed throughout the years. Many who served responded to the magic and thus remarkable things took place on a simple volunteer level. The belief was established by Grace McCann Morley, the first director of the San Francisco Museum of Art . Along with John Humphrey , a couple of typewriters, and a few prints and drawings from Albert Bender , the Museum began in its present surroundings. Most of all it began at the outset of a glorious period in the history of the art of the Bay Area. Grace Morley was firmly convinced of the importance of art and she gave generously to the local artists space in the Museum to show their works.”

During my nine years at SFMOMA, I spent a lot of time in the archives poring over inspirational moments in our history, trying to understand why they happened, how they were sustained, and how they could be replicated. A desire to make sense of the world is probably what drew me to this profession in the first place; there are so many factors for why a good thing doesn’t last or why good people have to leave. So I search for clues — even if the ability to make sense of things is little comfort when faced with colleagues losing their livelihood and the institution losing parts of itself.

This summer, my last at the museum, brought news of the end of the museum’s Artist Gallery, Film Program, Modern Art Council — and Open Space. It is hard to say goodbye to these foundational programs, and it seemed appropriate, as I, too, was leaving, to reflect on their creation and their contributions.

:strip_icc()/BHG_PTSN19720-33d9cd22f6ab49e6a21982e451321898.jpg)

More Stories

Mapping Eastern Europe Website Launched

Kengo Kuma Designs a Dramatically Vaulted Cafe to Evoke Japan’s Sloping Tottori Sand Dunes — Colossal

Keeping The Artist Alive | Chris Locke | Episode 888