[ad_1]

Curated by Anna Davis, the exhibition Ultra Unreal, which opened this week at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA), reflects on the relevance of contemporary mythmaking and its role in navigating complex realities and fluid frameworks of being.

We are not talking Hansel and Gretel-style mythmaking here; we’re talking AI avatars, gaming, queer club culture, and nightlife ecosystems. Realities, futurism and faith systems fuse with politics, technology and new world reality.

How does that play out in an exhibition? It is immersive, time snagging, at times unsettling, eye-candy strange, and future voyeuristic. Intrigued?

Davis explained: ‘All the artists in this exhibition are world builders. Some create elaborate sets, costumes and performances; others work with gaming technologies creating virtual worlds, and others are working with film and cinema to create episodic, and organically growing works that build over time to create a kind of expanding universe and cosmology.

‘It’s a collision of different things, rather than trying to sum it up in a few words,’ Davis continued.

‘These artists are not afraid to ask big questions in their work, [like] what happens after we die? They are really asking questions about the worlds that we want to create – and who gets to invent the future?’ she told ArtsHub.

Ultra Unreal comprises the work of six artists/collectives.

Saeborg (Tokyo) and Club Ate (Bhenji Ra and Justin Shoulder, Sydney) have emerged from the politics of the dancefloor and LGBTQIA+ club communities to simulate more-than-human futures.

‘Nightlife is something that’s often portrayed or framed in a way of just purely pleasure seeking. But I think one of the things that this exhibition tries to do is reflect on how these spaces and communities can be real incubators for ideas,’ explained Davis.

‘They’re also spaces that allow communities to perform other realities, and to imagine a different kind of future,’ she said.

Audiences walk into the gallery to confront Saeborg’s installation Slaughterhouse (2021-22), a vignette of latex farm animals in role play. They stand in for gender-based power roles and stereotypes in Japan in a commentary about society’s treatment and expectations of women.

Davis explains: ‘It really is a way to transcend her own body; to transcend gender and to reshape the body through latex … as a way of talking about these issues through a nonhuman lens.’

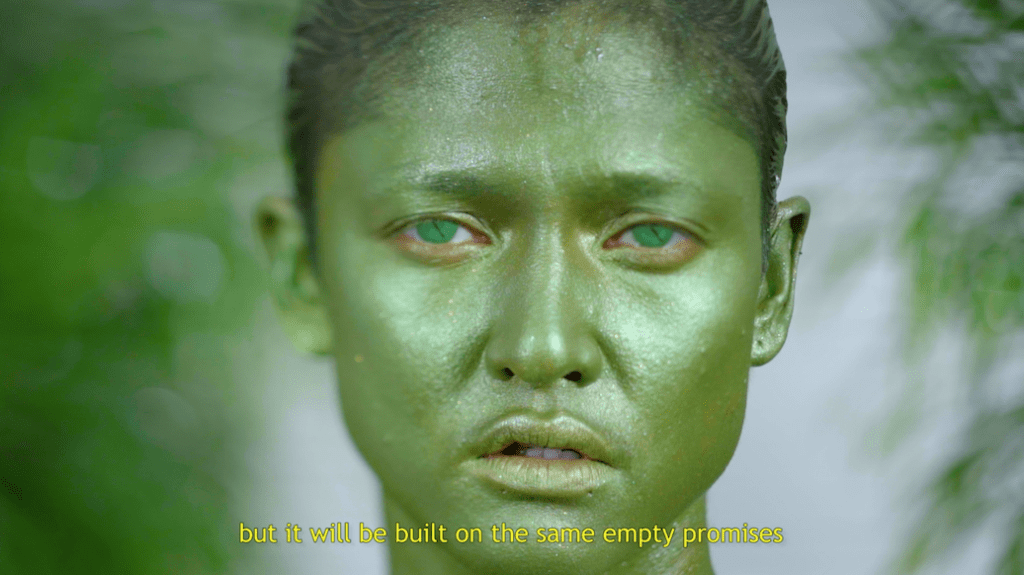

Also taking its cue from club culture, Club Ate’s two-channel video, Ang Idol Ko/You are My Idol (2022) combines Filipino mythologies and Babaylan (trans shamans in the Philippines) to act as ushers into future worlds.

Club Ate’s Shoulder explained: ‘We wanted to collapse that space between mythmaking and storytelling and the kind of investment in future folklore, grounding it in the now. We really wanted this film to kind of gesture towards community-based storytelling.’

In another space Lu Yang (Shanghai) merges Buddhist thought and iconography, pop culture, neuroscience and biology, asking viewers to contemplate whether consciousness can be manufactured and sustained beyond the life of the individual.

To explore these ideas, they use the avatar DOKU – a digital reincarnation of Lu in a parallel universe played out across six suspended screens. Visually, it is incredibly engaging.

Davis said: ‘As an artist who has repeatedly expressed their desire not to be labelled through gender, through nationality – through pretty much anything that we usually put on a exhibition label – Lu creates virtual worlds populated by simulated cells or avatars. They ask, “what happens to our consciousness after we die?”’

An avid gamer, Lu explores the idea of dying many times in one session and understands that in terms of everyday reality, life is ‘played’ out in perpetually evolving futures.

But where reality and futures imagined and pasts rethought really come together, is in the work of Korakrit Arunanondchai and Alex Gvojic (Bangkok and New York). Shown for the first time in Australia, No history in a room filled with people with funny names 5 (2018) is from a series of works developed over the past decade, which across three expansive screens moves from empathy to animism; from politics to contemporary Thai mythology.

The work takes its cue from knowledge systems and political propaganda, and tries to filter our mad world through Naga mythology and things like ghost cinema.

Davis explained the work picks up on the global news story of 2018 when 12 boys from a soccer team were trapped in a flooded cave in Thailand.

‘This is also a moment when Thailand really sought to reframe its image to the world…three of the boys went into the cave stateless; and then when they came out, they were Thai citizens.

‘So there’s this really interesting interconnection of mythology, propaganda, nationalism, all these kind of ideas coming together, but also connected to family and memory,’ Davis said.

The final work by Lawrence Lek (London) explores Sinofuturism, with the central figure a sentient weather satellites that dreams of being an artist. The work is set in Singapore in 2065 went all the oceans have risen due to climate change.

Davis noted: ‘Lek draws on his background in architecture, using gaming software and computer-generated imagery (CGI) to create artificial worlds.’

‘He is developing a way to create storytelling through architecture and CGI,’ said Davis. ‘And questions whether cyber futurism is itself a form of artificial intelligence.’

Davis continued: ‘There’s a really interesting thread moving through the exhibition of the way that these particular artists, who have all come in different ways from a performance background, create fantastical worlds, which we invite people to explore and enjoy.’

Some works take over half an hour to view, while others expand beyond the physical gallery spaces into virtual spaces at MCA accessed by a QR code on the Museum’s website. What is especially interesting about this exhibition is the way it questions how we imagine our future, and in doing so shape its very development.

Ultra Unreal is showing at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA) from 22 July to 2 October 2022.

The exhibition also offers daily screenings of video works by artists Lu Yang, Lawrence Lek, and Saeborg.

[ad_2]

Source link

:strip_icc()/BHG_PTSN19720-33d9cd22f6ab49e6a21982e451321898.jpg)

More Stories

Fresh and Airy Interior Design Living Room Ideas for Summer

Where Art and Sound Converge: Exploring Fine Art Photography and Music Artist Portraiture

Cooking Chinese Cuisine with Ease Using Jackery Solar Generator 5000 Plus