[ad_1]

When depicting life in rural England, artists had to decide whether their depictions would focus on the hard lives endured by the peasant workers or focus on the beautiful idyllic life folk had who managed to escape the industrialization of the cities. The artist I am looking at today was of the second group of painters who wanted to cast her artistic spotlight on the beauty of rural life and was well known for her depictions of country cottages. Let me introduce you to Helen Allingham.

Helen Mary Elizabeth Paterson was born into a well-to-do middle-class family on September 26th, 1848 in the small village of Swadlincote, near Burton on Trent in Derbyshire, England. She was the eldest of seven children born to Alexander Henry Paterson, a rural physician, and Mary Chance Herford, the daughter of a Manchester wine merchant. Within her first year of her life, the Patersons moved to Altrincham, Cheshire where Helen’s father set up a medical practice and the young family grew and prospered. It was during these years that young Helen’s interest and talent in art blossomed, inspired by her maternal grandmother, Sarah Smith Herford, a landscape painter and her aunt, Laura Herford, a professional and accomplished artist.

One of Laura Herford’s most endearing paintings is her The Little Emigrant which she completed in 1868. It depicts a young girl seated on the deck of a ship, with her head resting on her hands, her right arm on the ship’s railing. She has golden hair, wears a maroon dress with red and white striped neck scarf. The work was painted by Laura after her visit to Auckland and Nelson. The idea of the depiction is believed to be after Laura had listened to an account by a real emigrant to New Zealand on the siling ship, Lord Auckland, when as a child she remembered sitting for days and weeks on the seat that ran round the waist of the ship, under the high bulwarks, looking out over the wide, wide sea. She sat there dreaming of the homeland to which she would never return.

In her twenties Laura Herford was heavily drawn into the argument of the recognition and training of female artists. She signed the 1859 petition to admit women to the Royal Academy. She submitted several drawings to the Academy’s admissions tutors signed “L. Herford“. The use of initials masked her gender, leading to the assumption that she was a man. She was admitted on the merits of these drawings and an offer was made to “L. Herford, Esq” and she took up her place at the Academy in 1860 !!! She exhibited at the Royal Academy from 1861 to 1869 and also at the Suffolk Street Gallery and the British Institution. Later, she invited her sister’s daughter, the painter Helen Paterson Allingham, to come live with her in London at the start of her career.

Helen’s mother, Mary was also an artist but gave it up when she married. Helen’s father’s medical practice failed and the family moved out of the small rural community, which Mary never liked, and relocated to Altrincham, Mary’s hometown. Her husband purchased another medical practice in the town. The new practice thrived and soon the family could afford to have a house built in the countryside at Bowden.

Helen Paterson attended the Unitarian boarding school, once attended by her mother and which had been founded by her grandmother, Sarah Smith Herford. In May 1862, when Helen was aged thirteen, tragedy struck her family. Her father battled to treat local victims during a severe diphtheria epidemic. Dr. Paterson succumbed to the disease himself, along with Helen’s three-year-old sister Isabel.

Shortly after the death of the father, the young family moved to Edgbaston, Birmingham where their Paterson aunts helped house and feed them, but money was tight. As time passed, Helen’s artistic talents grew and she enrolled in the Birmingham School of Design. Here for fifteen shillings a term, she studied Drawing, Perspective, Practical Geometry and Painting, three times a week. After three years of study, Helen won the School’s Special Prize, given to her for her outstanding anatomical studies. The School was so impressed with her talent they advised her to apply to the Royal Academy Schools.

At age seventeen, Helen secured a place in the Royal Female School of Art in London. A year later, in 1867, she was accepted into the prestigious Royal Academy Schools, a door first opened to women by Helen’s aunt Laura just a few years before. The Royal Academy Schools boasted a number of highly thought of masters of the art world who visited and taught the students. Helen Paterson was influenced the most by the lectures and tuition given by Frederick Walker, Sir Frederick Leighton, and Sir John Everett Millais, who was a co-founder of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. The tuition at the Royal Academy was free, but Helen still needed money to pay for her accommodation and living expenses. With that in mind, she sought work with engraving firms, sketching figures and scenes in black & white, and in 1869 was commissioned by the Once A Week magazine, a weekly illustrated literary magazine to contribute four full-page illustrations. Her work was well received, and this led to more commissions by other periodicals and children’s books while she continued her schooling three days a week.

In 1870, twenty-two-year-old Helen was hired as one of the founding staff members, and the only female, on The Graphic, a British high-quality weekly illustrated newspaper, first published in December 1869. During the next three years, commissions to illustrate books and periodicals continued to pour in and by 1872 Helen decided to give up her schooling at the Academy and work as a commercial artist. Some of her most important commissions included illustrations for Thomas Harding’s fourth novel, Far From the Madding Crowd which was first published in 1874.

Two sudden and unexpected deaths in the early 1870’s greatly saddened Helen. In October 1870 she was summoned from her lodgings by William De Morgan who was concerned that his fellow lodger at Fitzroy Square, Laura Herford, had not been seen that day. He knew that Helen was a relative of Laura Herford and so when the two went back and entered Laura’s lodgings they found her lying dead in bed. She had been suffering from constant toothache and be self-medicating with morphine and it was thought that she had died from an accidental overdose. She was thirty-nine-years-old.

One year later, in November 1871 Helen was summoned home. On returning to the family in Cheshire she was told that her eighteen-year-old sister Louisa was dying of consumption. There was little Helen could do but help the family at this sad time and sit with her sister and help her mother nurse her dying sister. During the times Helen sat at her sister’s bedside she made several pencil sketches of Louisa and one small and emotional watercolour of her.

Now in London and because of her commissions, Helen’s circle of friends grew and she came into contact with prominent writers and artists. One such friend was William Allingham, the editor of Fraser’s Magazine. William Allingham was born on 19 March 19th 1824 in Ballyshannon, a small town in the south of County Donegal in Ulster in the north of Ireland, which is now in the Republic of Ireland. He was the son of the manager of a local bank who was of English descent. When William was nineteen, he became a Customs officer, and he was stationed at different places in Northern Ireland until he was thirty-nine years old. Shortly after he obtained his appointment with the Customs, he made his first trip to London and after that first visit, made many more to the English capital. He would submit many articles to London’s periodicals. He retired from the Civil Service in 1870 and moved to London and sub-editor of Fraser’s Magazine under J. A. Froude, whom he succeeded as editor in 1874. It was also in 1874, on August 22nd, that Allingham and Helen Paterson were married after the briefest of engagements. He was fifty and she was a month away from her twenty-sixth birthday. William Allingham had developed many good friends in London’s literary and artistic circles such as Thomas Carlyle, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Robert Browning, John Ruskin, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

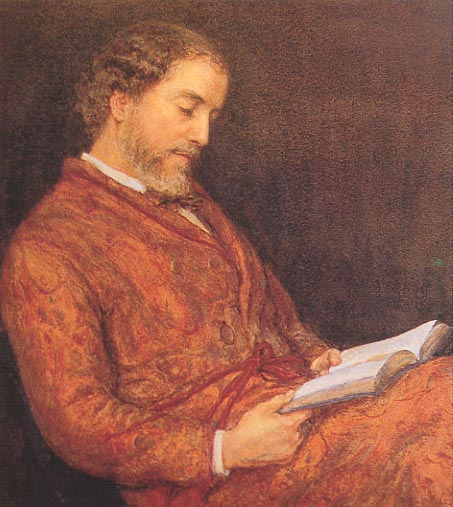

A few months after their marriage, Helen Allingham painted a portrait of her husband.

The newly weds went to live in a house at Trafalgar Square, in the borough of Chelsea, close to William Allingham’s best friend, the Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher, Thomas Carlyle. Such was their close friendship that William had taken Helen to visit Carlyle before they married, just to make sure Carlyle approved of his choice of wife ! Helen and William became regular visitors to Thomas Carlyle’s home in London and after many preliminary sketches completed a painting of their good friend. Look at how Helen has incorporated all the details of the furnishings of Carlyle’s room.

Helen’s other paintings depicted the interior of Carlyle’s rooms at his residence in Cheyne Row London. It is said that such an accurate depiction of the room aided the National Trust when they came to the restoration of the room.

Married life suited Helen and she no longer had to go out to work. She gave up her position at the Graphic and in a way she had been pleased to have worked at the journal for four years and it had allowed her to regularly send money to her mother. Although working for the Graphic had been advantageous, Helen was pleased to be able to concentrate on her paintings, especially her watercolours and she did manage to do some freelance book illustrations for novels written by her friends, George Elliot, Thoams Hardy and Tennyson.

In November 1875 Helen gave birth to her first child, a son, Gerald Carlyle named after her and her husband’s good friend. In February 1877 a second child, a daughter, Eva Margaret, was born. Her third child, a son, Henry William was born in 1882. He was the love of Helen’s life and she would often wear a locket with just his picture inside. In 1874 Helen Allingham had two of her watercolours, The Milkmaid and Wait for Me, exhibited at the Royal Academy and in 1875 she was put forward by the eminent watercolourist, Alfred Hunt, to become an Associate in the Royal Watercolour Society. She was later to become the first woman to be admitted to full membership.

Her early work tended to feature large figures in a landscape, but later, influenced by their holidays in the country, her style shifted more to smaller figures with emphasis on the rural scene itself. During the seven years the Allinghams lived in London, Helen exhibited more than a hundred watercolours, some depicting her own children as models. During her early days, Helen produced rural depictions featuring large figures. However, in her later paintings she focused on the inanimate and nature itself and any figures depicted were much smaller.

On February 5th 1881, after a short illness, Helen and William’ close friend, Thomas Carlyle died, aged 85. His death came as a terrible shock to them and now that he was not a close neighbour any more, they felt no reason to stay in the English capital. They decided to move into the country and settled in the small Surrey hamlet of Sandhills. It was from this new base that Helen developed the love of depicting pretty cottages. Sandhills proved to be an idyllic and peaceful resting place for both Helen and William. He was able to spend time writing poetry and Helen passed the hours painting watercolours depicting the rural areas around their home, the numerous pretty flower gardens, her children as they grew up and of course the “chocolate-box” country cottages which were all around where they lived. As the boom of industrial development continued to threaten traditional rural life, Allingham’s paintings captured unblemished landscapes and historic cottage architecture in superb detail. Helen was fervently concerned for the preservation of the English countryside and this love of hers was also held by the viewing public. In 1886 Helen was invited by the Fine Arts Society to hold a one-woman exhibition with the title Surrey Cottages.

Helen’s depiction of the old, thatched cottages was not just an act of sentimentality but it was to remind people of what life was like before the railways built their tracks through acres of beautiful land and with the arrival of the railways came the hordes of middle-class families into rural communities. Some bought the cottages and refurbished them while others demolished them and built modern monstrosities. For Helen, the task was to memorialise the beauty and tranquillity of rural life and the exquisiteness of the country cottage which she depicted with such accuracy. She would roam the countryside and paint en plein air the cottages which were marked for demolition. She would add small figures to the scenes and sometimes would substitute thatch rooves to depictions of cottages which had been modernised with man-made materials but at the same time tried to avoid the idealistic depictions.

In 1888, Helen’s husband William became ill with persistent indigestion and the couple decided to move away from the countryside and return to London to be close to family friends. They took up residence in Hampstead in a large home in Eldon Road. William Allingham’s health continued to deteriorate and despite an operation in the Spring of 1889, he died that November, aged 65, leaving Helen, then forty-one, to support herself and three young children, aged fourteen, twelve, and seven. In 1891 Helen and her children travelled to the Irish town of Ballyshannon where their father, William was born and laid to rest. A monument had been erected in honour of their late father and Mary took the opportunity to visit some of his relations. She also painted a number of watercolours of the landscape and the peasant cottages.

In 1890 the Royal Society of Watercolours opened their membership to women, and Helen had the honour of being the first elected into the Society. Helen exhibited her scenic country watercolours every year in London and her depictions of rural cottage scenes grew in popularity. In 1903 Helen collaborated with Marcus B. Huish for a book about English country life titled Happy England, which featured eighty colour plates of Helen’s watercolours.

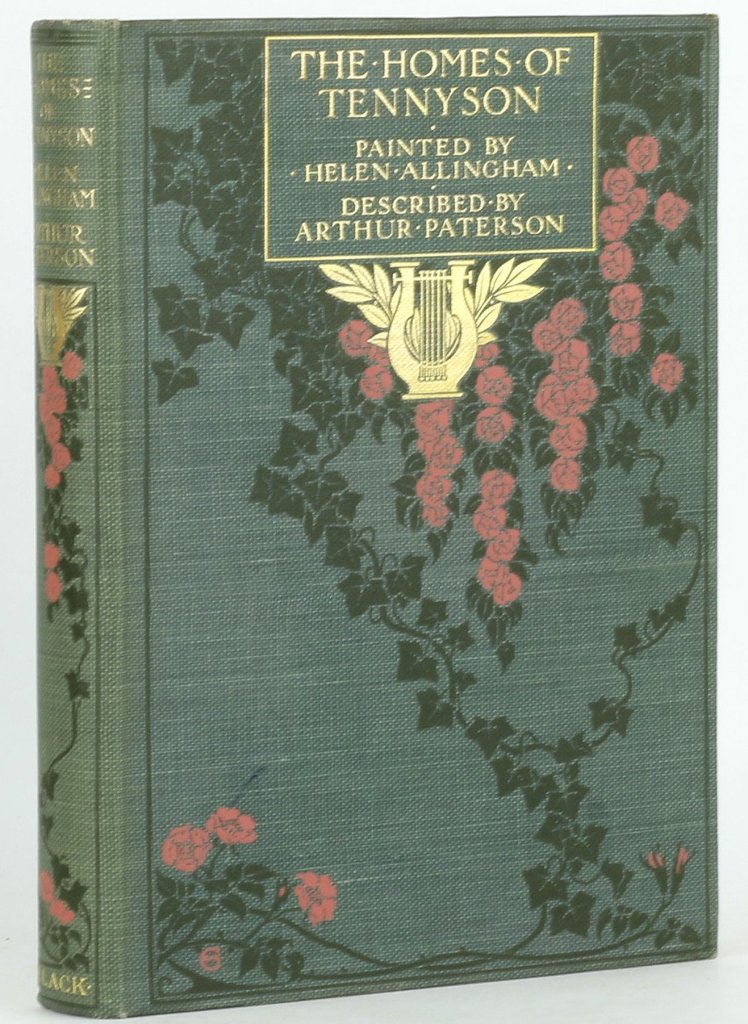

In 1905 she and her brother, Arthur Paterson, collaborated to produce a book entitled “The Homes of Tennyson” which contained twenty of her paintings. More books followed including editing several books of her late husband’s poetry. Helen continued to paint and exhibit her work. On September 28th, 1926, two days after her seventy-eighth birthday, Helen Allingham died of a acute peritonitis while visiting an old friend at Valewood House in Haslemere, just a few miles from her old country home in Sandhills.

Most of the information for this blog came from the

[ad_2]

Source link

:strip_icc()/BHG_PTSN19720-33d9cd22f6ab49e6a21982e451321898.jpg)

More Stories

Mapping Eastern Europe Website Launched

Kengo Kuma Designs a Dramatically Vaulted Cafe to Evoke Japan’s Sloping Tottori Sand Dunes — Colossal

Keeping The Artist Alive | Chris Locke | Episode 888