The world is full of genuine fakes: the objects that fall into the space between things that are real and those that are not. Whether or not we think things are authentic is a matter of perspective. From stories of audacious forgeries to feats of technological innovation, historian and writer Lydia Pyne explores how the authenticity of genuine fakes from art forgeries to synthetic flavors depends on their unique combination of history, science and culture.

Hello Lydia, how did you get the idea to write this book?

My background is in paleolithic archeology and history of science, and those are the topics I have written about. While I was working on one of my previous books, about famous fossils, I had the opportunity to research a fake fossil. It’s called the Piltdown hoax and when I saw it at the Natural history Museum in London, it struck me how interesting it was that this fossil is made of real pieces of bones that are put together to make a fake species.

I was so struck by this juxtaposition that you can have real things but they can add up to be something fake at the end. So I was curious to explore this question of materialism, what is this thing made of and how does it contribute to how we think about it. And how it happens to it as time goes on.

So I looked for other genuine fakes and I started to find them everywhere! I wanted to put together a project that looked at authenticity as a continuum. To look at how an object can change overtime.

So what is a genuine fake?

Well it can go from artificial flavoring to man made diamonds, detailed reproductions of Paleolithic living spaces (like Lascaux caves) or some artworks combining fabrication and veracity.

There is for example, the case of William Henry Ireland whose knack in the late 18th century for locating documents signed by Shakespeare was uncanny as well as profitable.

Ireland even “discovered’ a long-lost play, Vortigern and Rowena. He eventually confessed to having concocted his “discoveries” in order to get money out of his father. Even after Ireland’s confession, some people were either gullible or ironic enough to want to own the spurious documents, which gave him an incentive to forge copies of his own forgeries.

Today William Henry Ireland is one of the most collectable and valuable of the dubious pantheon of Shakespearean forgers, with authentic Irelands fetching anywhere from a few hundred pounds to tens of thousands of pounds at auction. William Henry Ireland’s forgeries continue to intrigue scholars. Institutions that have Ireland holdings consistently find their Ireland forgeries in use for any number of scholarly research projects.

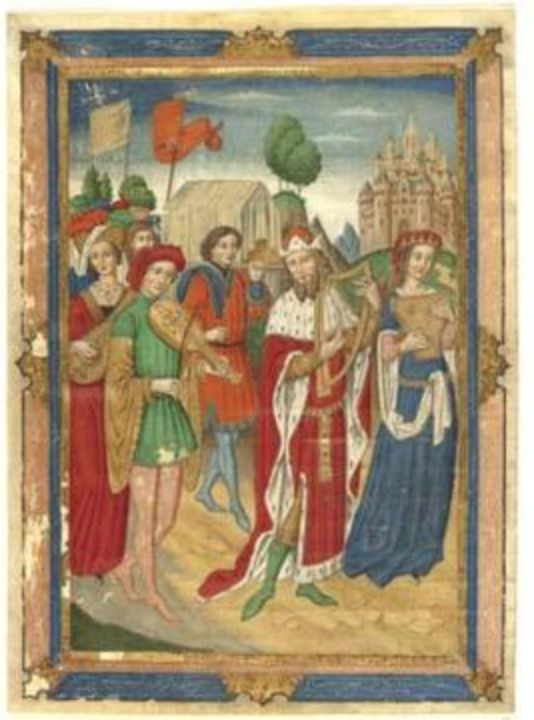

One of the other really fun examples was this artist named the Spanish Forger who in the 19th century created amazing medieval artworks. It’s not medieval but it’s how buyers at the time wanted to think about the medieval era with knights in shiny armors. When his work was debunked in the 1930’s it was relegated as fake. In the following decades, they become their own thing and collectable.

It shows that how people think about it, evolved through time.

Can you share another example of an object whose status changed over time?

We can think about a famous artefact named the Grolier Codex. Its story is quite interesting: The conquistadors who swept through the Mayan empire in the 16th century burned every text they could find, apart from three codices sent home as souvenirs and curiosities. First shown in public in 1971 after being discovered in Mexico, the Grolier Codex was generally assumed to be part of the enormous body of fake Mayan books sold to collectors throughout Europe and the Americas over the centuries. An analysis of the composition of one of the paints used in the codex suggests that it is genuine but skeptics remain. This story of the Grolier Codex is a reminder that objects live on a continuum of authenticity, and that they can move up and down that continuum, depending on their history and context.

So how to evaluate what is the real thing?

Before we demand that something be authentic or dismiss something as fake, we ought to think about the purpose, intent and context of the object in question and what we would accept as the Real Thing.

You have a new book coming up in December, can you tell us about it?

The book is “Postcards: The Rise and Fall of the World’s First Social Network”.

Postcards are usually associated with banal holiday pleasantries, but they are made possible by sophisticated industries and institutions, from printers to postal services. When they were invented, postcards established what is now taken for granted in modern times: the ability to send and receive messages around the world easily and inexpensively. Fundamentally they are about creating personal connections—links between people, places, and beliefs. The book examines postcards on a global scale, to understand them as artifacts that are at the intersection of history, science, technology, art, and culture. Postcards were the first global social network and in the twenty-first century, they are not yet extinct.

Follow her on twitter

:strip_icc()/BHG_PTSN19720-33d9cd22f6ab49e6a21982e451321898.jpg)

More Stories

Gurney Journey: USA Today Recommends Dinotopia

“From Generation to Generation…” — A Sanctified Art

The Public Theater’s Under The Radar Festival Lights Up NYC This January