Belgian gallerist Xavier Hufkens has inaugurated his renovated, four-story space in Brussels with an extensive solo show dedicated to the American artist Christopher Wool, marking their first project together and Wool’s first show in Belgium since 2009.

On view are Wool’s abstract paintings, which combine silkscreening and other processes; black-and-white photographs of Marfa, Texas, where he lives, as well as New York; and small- and large-scale sculptures. Many of the works were made during the past two years of relative isolation.

“Having Texas to go to was a great freedom,” Wool, who rarely speaks to press, told Artnet News. “It allowed me to work quietly which I don’t always get to do. I was able to work more than pre-pandemic.”

Installation view, “Christopher Wool” at Xavier Hufkens. Photo credit: HV-studio

What’s striking about the exhibition are the relationships between the different media. While the artist is known primarily for painting, the show suggests that sculpture and photography are also highly important to his practice—and that these forms of expression are all deeply interconnected.

The photographs, devoid of people, capture discarded objects, batches of tires, and arid landscapes. Typological in nature, they carry a sense of bleak emptiness.

Then there are small sculptures made from twisted barbed wire that Wool found at ranches. Wool has elevated their humble materiality by showing them on plinths. Larger sculptures expand on those ideas, including some some made from copper-plated bronze or assembled from 3D-printed elements. Asymmetrical and irregular, they bear a relationship to Wool’s over-layered paintings, featuring colored lines and smeared shapes.

Dressed in a red-and-black checked shirt, dark trousers, and yellow-and-gray sneakers, his silver hair swept back into a ponytail, 67-year-old Wool cut an unassuming presence as he talked about his foray into sculpture.

“When I first went to Marfa 15 years ago, it struck me right away that making sculpture was a rich possibility, but I did not have sculptural ideas,” Wool recalled.

Christopher Wool, Untitled (2017). Copyright Christopher Wool.

He started collecting fencing wire from local ranches without knowing how he might use it. “I immediately saw that it mirrored my sense of drawing,” he said. “I was collecting the wire before I was really thinking about making sculpture.”

Conspicuously absent from the exhibition are the kinds of stenciled text paintings which made Wool famous in the ’90s—and set his auction record seven years ago. In 2015, the painting Untitled (Riot) (1990), its capital letters written in enamel, went under the hammer for $29.9 million at Sotheby’s.

This was the peak of the artist’s market, two years after his solo exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. Demand for Wool’s work has contracted substantially since then. Indeed, he could be seen as a casualty of shifting tastes from abstraction to figuration and a market that is now less likely to undervalue works by female artists and artists of color.

Installation view, “Christopher Wool” at Xavier Hufkens. Photo credit: HV-studio

Hufkens, however, is undaunted by those market factors.

“The first time that I got in touch with Christopher Wool was 1996,” Hufkens said. “His work has been in my mind for many, many years. I thought that it would be the perfect combination [for the revamped gallery], perfect with the architecture—a perfect marriage.”

Born in 1955 in Boston to a molecular biologist father and a psychiatrist mother, Wool grew up in Chicago and moved to New York at the height of the punk movement in the ’70s. His early work was imbued with anarchic energy and influenced by urban aesthetics, advertising, rock n’ roll, and graffiti. Despite his success, the self-deprecating Wool says that he does not regard his works as “masterpieces.”

“Post-modernism is not [about] making masterpieces, but making paintings that are interesting on a different level,” he said. “In [American critic] Clement Greenberg’s idea of Modernism, there was a model of what you were supposed to follow. I think it’s proven to be much more open and interesting than that.”

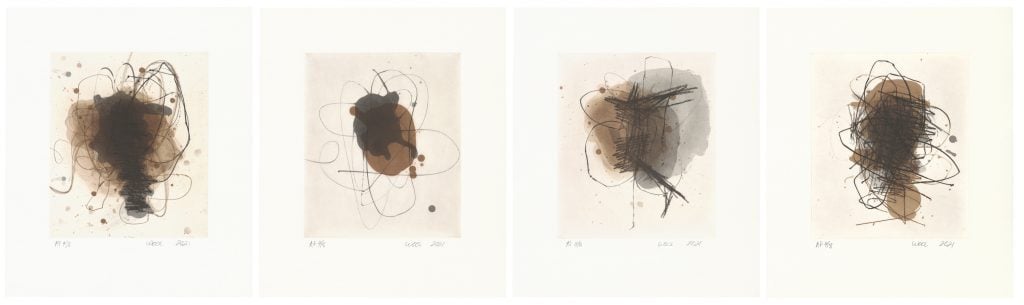

Christopher Wool, Untitled (2021). Copyright Christopher Wool.

Wool admitted that although his work is relatively simple on a technical level, it still produced bouts of anxiety.

“You can make a decision to go forward with the painting and regret it, and you can make the decision to not go forward and regret that, too,” he conceded. “My wife [the German artist Charline Von Heyl] and I have a running gag: If you come home from the studio and think, ‘I’ve had a good day,’ things will not work so well the next. And if you come home and think everything went poorly, it’s got to go better the next day.”

Wool appeared characteristically subdued about the Brussels exhibition. But gazing around the show, spread out in Hufkens’s fluid, gray concrete space by Belgian architecture firm Robbrecht & Daem, his satisfaction was evident. “Having four floors, each with a different character,” he said, “is ideal for the show.”

“Christopher Wool” is on view at Xavier Hufkens, 6 rue St-Georges, Brussels, Belgium, from June 2 to July 30, 2022.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

:strip_icc()/BHG_PTSN19720-33d9cd22f6ab49e6a21982e451321898.jpg)

More Stories

Fresh and Airy Interior Design Living Room Ideas for Summer

Where Art and Sound Converge: Exploring Fine Art Photography and Music Artist Portraiture

Cooking Chinese Cuisine with Ease Using Jackery Solar Generator 5000 Plus