[ad_1]

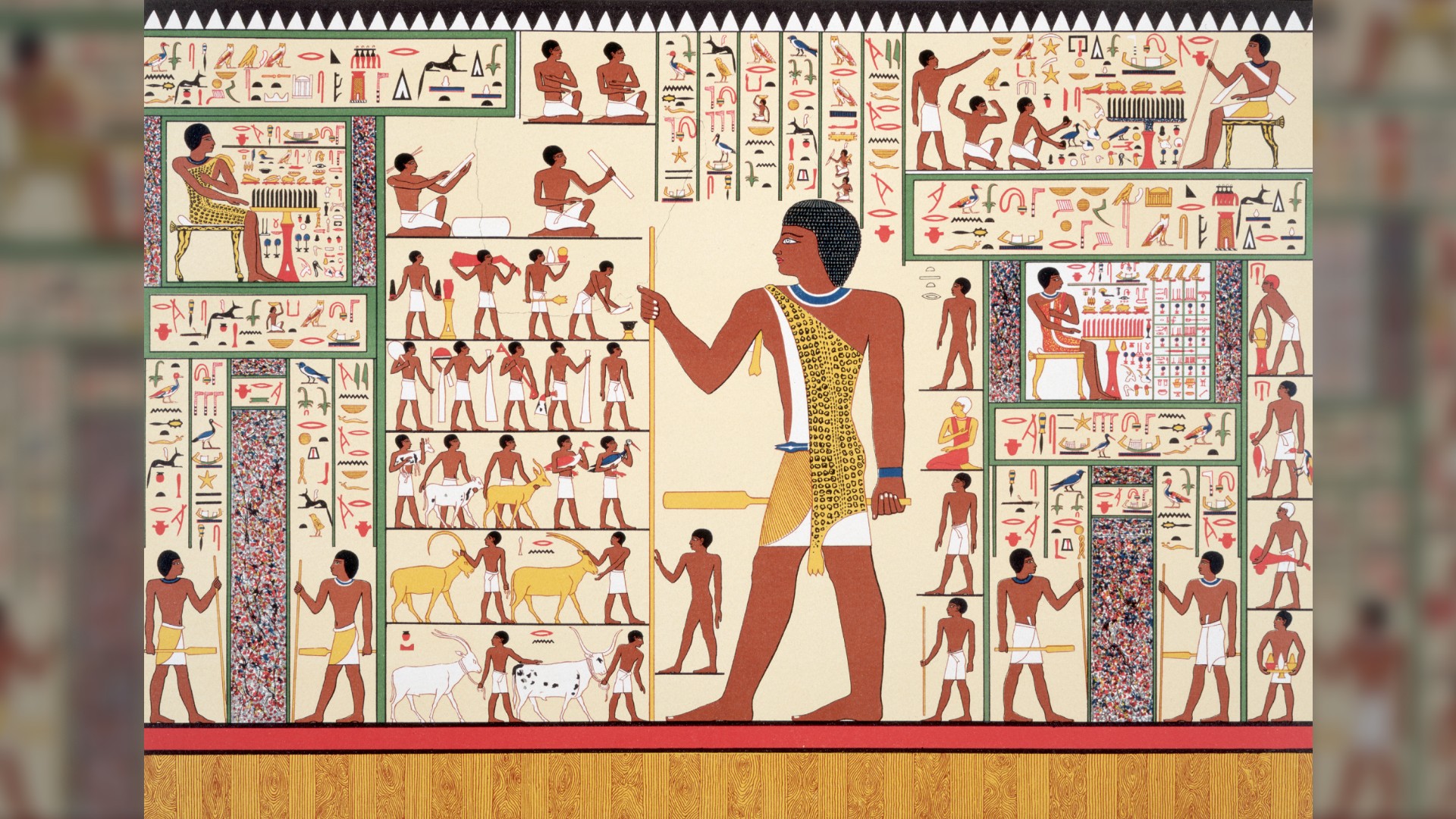

In 1986, the band “The Bangles” sang about “all the old paintings on the tombs” where the figures they depict are “walking like an Egyptian.” Though he was neither an art historian nor an Egyptologist, songwriter Liam Sternberg was referring to one of the most striking features of ancient Egyptian visual art — the depiction of people, animals and objects on a flat, two-dimensional plane. Why did the ancient Egyptians do this? And is ancient Egypt the only culture to create art in this style?

Drawing any object in three dimensions requires a specific viewpoint to create the illusion of perspective on a flat surface. Drawing an object in two dimensions (height and breadth) requires the artist to depict just one surface of that object. And highlighting just one surface, it turns out, has its advantages.

“In pictorial representation, the outline carries the most information,” John Baines, professor emeritus of Egyptology at the University of Oxford in the U.K. told Live Science. “It’s easier to understand something if it is defined by an outline.”

Related: What did ancient Egypt’s pharaohs stash inside the pyramids?

When drawing on a flat surface, the outline becomes the most important feature, even though many Egyptian drawings and paintings include details from several sides of the object. “There is also a great focus on clarity and comprehensibility,” Baines said.

In many artistic traditions, “size equals importance,” according to Baines. In wall art, royalty and tomb owners are often depicted much larger than the objects surrounding them. If an artist were to use a three-dimensional perspective to render human proportions in a realistic scene with a foreground and background, it would go against this principle.

The other reason for depicting many objects on a flat, two-dimensional plane is that it aids the creation of a visual narrative.

“One only has to think of [a] comic strip as a parallel,” Baines said. There are widely accepted principles that organize how ancient Egyptian visual art was created and interpreted. “In origin, writing was in vertical columns and pictures were horizontal,” Baines said. The hieroglyphic captions “give you information that is not so easily put in a picture.” More often, these scenes don’t represent actual events “but a generalized and idealized representation of life.”

However, not all pictorial representation in ancient Egypt was purely two-dimensional. According to Baines, “Most pictorial art was placed in an architectural setting.” Some compositions on the walls of tombs included relief modeling, also known as bas relief, in which a mostly flat sculpture is carved into a wall or mounted onto a wall. In the tomb of Akhethotep, a royal official who lived during the Fifth Dynasty around 2400 B.C., we can see two scribes (shown below) whose bodies are sculpted into the flat surface of the wall. As Baines explained, the “relief also models the body surface so you can’t say that it’s a flat outline” because “they have texturing and surface detail in addition to their outlines.”

In many examples dating as far back as 2700 B.C. in the Early Dynastic Period, artists painted on top of a relief to add even more detail, as seen in the image of the two scribes below.

Egyptian visual art used “more or less universal human approaches to representation on a flat surface,” Baines said.

“It [Egyptian art] influenced art in the ancient Near East,” such as ancient Syrian (or Levantine) and Mesopotamian art, Baines said. The same conventions can be seen in many other ancient traditions of art. Maya art also uses pictorial scenes and hieroglyphic script. Although classical Greek and Roman art is an exception, there are even examples of similar artistic conventions for two-dimensional drawing and painting from medieval Europe. As Baines explained, “It’s a system that works very well and so there’s no need to change it.”

Originally published on Live Science.

[ad_2]

Source link

:strip_icc()/BHG_PTSN19720-33d9cd22f6ab49e6a21982e451321898.jpg)

More Stories

Fresh and Airy Interior Design Living Room Ideas for Summer

Where Art and Sound Converge: Exploring Fine Art Photography and Music Artist Portraiture

Cooking Chinese Cuisine with Ease Using Jackery Solar Generator 5000 Plus