[ad_1]

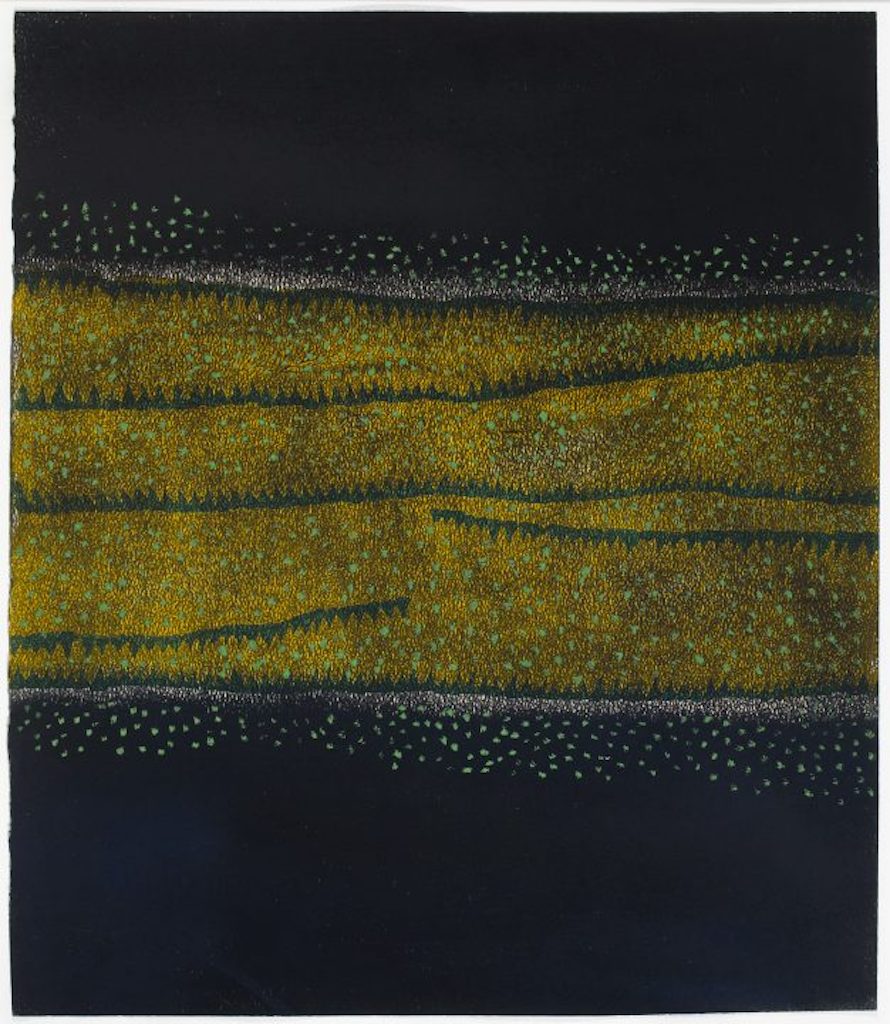

That arc is then illustrated in the five works on display, which comprise a tidy summary of Kusama’s evolving practice. Indeed, several of her abiding interests are already implicit in The Hill, 1953 A (No. 30) a small painting executed shortly after her first solo show. A swarm of stippled dots partially obscures a central band that features six wobbly lines comprised of wedge-like forms, which meander across the composition.

Evoking both a quiet, nocturnal landscape and an enlargement of a capillary or a tree’s fibrous cell, the painting thus suggests two irreconcilable scales. Moreover, while the irregular dots and triangles embody a tender handmadeness, they also speak to the artist’s effort to process her anxiety and recurring psychotic episodes through sheer repetition: a tactic that would soon become central to Kusama’s practice.

In the next room, Pumpkin, a 2016 piece, represents the maturation of those ideas. During a childhood trip to a seed-harvesting ground, Kusama was apparently struck by what she would later call the “solid spiritual balance” of a pumpkin; this sizable piece is one in a series of subsequent odes to the fruit. It’s also, though, a charming riff on the dour seriousness of Minimalist works. Like, say, Walter De Maria’s Cage II, Pumpkin is slightly taller than us and it sits directly on the gallery floor, in the middle of the room. Precisely applied rows of acrylic dots line its folds, in an exacting geometry. But the emphatically representational aspect, the softly organic curves, and the vibrant yellow-orange combine to create an endearing energy: something closer to Totero than Tony Smith.

Drift through the subsequent transitional space (which features a modest slide show and a forgettable inspirational poem that Kusama penned in the early days of Covid), and you arrive at the first infinity mirror room. Step inside the brightly lit, windowless container, and you’re surrounded by a bevy of handsewn tubular forms covered in red polka dots and reflected in the room’s mirrored walls.

Are those phallic forms disturbing symbols of masculine aggression? intimate products of craft and care? Critical reactions have varied. Regardless, the power of the space primarily resides in the relationship between the idea of self-obliteration and the use of mirrored repetition. As we see our own image multiplied, our very sense of self is eroded: a familiar tension, perhaps, in this era of virtual reproduction and self-promotion.

[ad_2]

Source link

:strip_icc()/BHG_PTSN19720-33d9cd22f6ab49e6a21982e451321898.jpg)

More Stories

Mapping Eastern Europe Website Launched

Kengo Kuma Designs a Dramatically Vaulted Cafe to Evoke Japan’s Sloping Tottori Sand Dunes — Colossal

Keeping The Artist Alive | Chris Locke | Episode 888