Years before Jackson Pollock was immortalized in the pages of Life magazine—cigarette dangling from his mouth, flinging paint across a canvas on his studio floor—Janet Sobel created her own unique drip paintings. A Ukrainian immigrant and mother of five, Sobel lay down in her Brighton Beach apartment, still wearing her high heels and stockings, while paint spilled lazily from her brush onto a canvas beneath her.

A 1949 picture by the photographer Ben Schnall captures Sobel in just this sort of creative moment, her face patient and observant, a perfect foil to Pollock’s tumultuous energy. Schnall snapped the image, according to some accounts, for inclusion in a Life magazine article about Sobel that never materialized. Its very existence, however, hints at the stature Sobel had earned in the 1940s, just a handful of years after she had started painting.

Unlike Pollock, today Sobel’s name and work are largely unfamiliar outside of the art historical circles that celebrate her. But she appears to be slowly returning to the narrative of American Modern art. Recently, the Museum of Modern Art in New York unveiled a gallery rehanging of work by Ukrainian-born artists, including Sobel, whose 1945 drip canvas Milky Way appears alongside pieces by Louise Nevelson, Kazimir Malevich, and Sonia Delaunay. Sobel’s art has, in recent years, been featured in blockbuster exhibitions such as “Women in Abstraction” at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris last year, as well as in “Abstract Expressionism” at the Royal Academy, London, back in 2016.

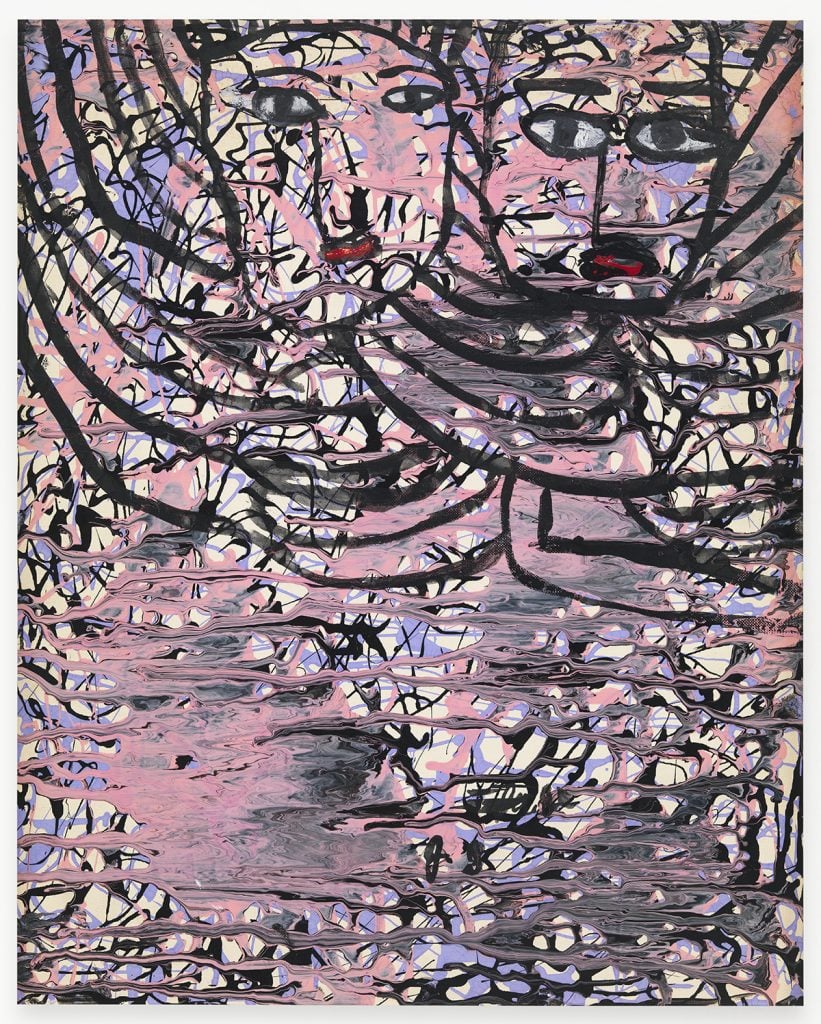

Janet Sobel, Untitled (JS-068) (c. 1946-48). Courtesy of Gary Snyder Fine Art MT

Sobel’s life story is like something out of a novel. She was born Jennie Lechovsky in 1893, to a Jewish family living near Ekaterinoslav (now Dnipro, Ukraine). Her childhood was marked by turmoil and tragedy. Her father, Bernard Lechovsky, was killed in a pogrom when she was very young. In 1908, her mother, Fanny Kahn Lechovsky, a midwife, emigrated with Sobol and her two siblings to the U.S, settling in New York.

In her adopted country, Jennie became Janet, and by the age of 16, she had married Max Sobel, a Ukrainian-born goldsmith with a costume jewelry business. The couple would have five children over the years. Though Sobel had little formal education, she was culturally minded and was supportive of her children’s interests in art, music, and literature.

When she did start experimenting with art-making—well into her 40s—Sobel was highly influenced by the power of music. Stories vary slightly, but Sobel’s start as an artist came at the urging of her son Sol. Still in high school, he had won a scholarship to the Art Students League but considered giving up art, much to his mother’s dismay. Frustrated, he said that she might try making art if she was so invested in it. When she did, Sol was amazed by her talents.

Her early works, dating to the late 1930s, harken to a self-taught primitivism reminiscent of both Jean Dubuffet and the magical charm of Marc Chagall’s visions, but always marked by Ukrainian folkloric touchpoints.

Sol became her greatest advocate, reaching out to artists like Max Ernst and his son Jimmy, and André Breton, about her works. The famed dealer Sidney Janis became an avid supporter, exhibiting her paintings in the 1943 exhibition “American Primitive Painting of Four Centuries” at the Arts Club of Chicago, where she was shown alongside other self-taught artists including Horace Pippin and Grandma Moses.

From this nascent style, Sobel moved toward her own distinct amorphic Surrealism. These images catapulted her into short-lived stardom. In 1944, she was included in a Surrealist group exhibition at Norlyst Art Gallery in New York, curated by Eleanor Lust and Jimmy Ernst, as well as an exhibition at Puma Gallery. A critic wrote at the time that “Mrs. Sobel is a middle-aged woman who only recently took up her brushes. The results are rather extraordinary. This is not conventional primitivism in any sense of the word.”

Peggy Guggenheim also took a liking to her paintings, including Sobel in the 1945 exhibition “The Women”, at her Art of This Century gallery, alongside the likes of Louise Bourgeois and Kay Sage. The following year, in 1946, Guggenheim gave Sobel the only solo show of her lifetime. “Janet Sobel probably will be eventually known as the most important Surrealist painter in this country,” the dealer Sidney Janis wrote during this period. He also noticed her shift towards the gestural freedom of her new drip paintings, saying: “More and more her work is given over to freedom and imaginative play. Her autodidactic techniques in which automatism and chance effectively predominate, are improvised according to inner demands.”

Her methods were anything but conventional. Sobel was known to have used glass eye droppers to splatter her paints, and at times employed the suction of her own vacuum to pull paint across the canvases laid out on the floor of her Brighton Beach home.

Pollock was familiar with Sobel’s work, having seen her paintings while visiting an exhibition with critic Clement Greenberg [Greenburg recalls seeing the works in 1944, which would likely have her show at Puma Gallery, a space run by the surrealist Ferdinand Puma and not the Guggenheim show which took place the following year].

Greenberg would write of the encounter: “Back in 1944, [Pollock] had noticed one or two curious paintings shown at Peggy Guggenheim’s by a ‘primitive’ painter, Janet Sobel (who was, and still is, a housewife living in Brooklyn). Pollock (and I myself) admired these pictures rather furtively—the effect—and it was the first really “all-over” one that I had ever seen, since Tobey’s show came months later—was strangely pleasing. Later on, Pollock admitted that these pictures had made an impression on him.”

Janet Sobel, Death Takes a Holiday (1945). Courtesy of the Museum + Gallery of Everything.

But despite that critical acknowledgment, Sobel was soon forgotten by the New York art scene. In 1946, She would move to Plainfield, New Jersey, where she was effectively cut off from her contacts in New York. She would continue to paint into the 1960s and exhibit her works locally.

Her sudden obscurity was also the result of the critical consternation that followed Sobel.

“Sobel’s work did not fit easily into any of the categories of the burgeoning 1940s New York art world or alternately it slid into too many of those categories. Sobel was part folk artist, Surrealist, and Abstract Expressionist, but critics found it easiest to call her a “primitive.” Greenberg’s endorsement functions ambivalently it lends credence to Sobel’s aesthetic accomplishments but safely sequesters her work,” wrote art historian and professor Sandra Zalman in an essay on Sobel’s work.

Dealer Gary Snyder has been an advocate of Sobel’s work for decades, first seeing it in the exhibition “Abstract Expressionism: Other Dimensions” at the Zimmerli Art Museum of Rutgers University in 1989. “What struck me was the quality of the work, which was equal to that of Pollock, and of the same era,” said Snyder, who organized a pivotal exhibition of Sobel’s work in 2002, the first solo show of her work since her exhibition at Guggenheim’s exhibition in 1946.

Snyder feels that, for many, Sobel simply didn’t fit with the narrative being built up around the New York School of painters so she was written out of its origin story. “Those years, the reputation of New York School of Abstract Expressionism was burgeoning with these bad boys of Jackson Pollock, and Willem de Kooning. Janet Sobel didn’t fit into that myth of powerful hard-drinking painters of big paintings. The attention went elsewhere.”

At the very end of her life, in 1966, the art historian William Rubin, then a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, would visit a bedridden Sobel while researching the work of Jackson Pollock. Rubin would there select two all-over abstractions by the artist to be brought into MoMA’s collection, one of which, Milky Way, is currently on view at the museum.

Beginning in the late 1980s, there has been a steady reappraisal of Sobel’s work, particularly in the past 15 years. Still, those conversations have largely centered on her drip paintings and their relationship to Pollock.

“Her stored experiences are what led to the spiritual, humanist, and profound nature of her art. When we visit MoMA and see The Milky Way, we realize that this is more than a painting—it is a message, to us, the viewers,” said James Brett, founder of the Gallery of Everything, London, which presented a booth devoted to Sobel’s work at Frieze Frieze Masters 2022, featuring five works seen in the background of the Ben Schnall photograph.

Today, Sobel’s oeuvre feels prescient and important for reasons well beyond exhausted conversations about the origins of Abstract Expressionism. Indeed, the folkloric qualities of her earliest paintings and her deep involvement in an American Surrealist style led largely by women feel particularly relevant to larger questions about the telling of art history. She remains quite singular in that regard.

“She’s a very unusual self-taught artist in that unlike most self-taught artists, her work evolved over time, like more Modern artists,” said Snyder. “She moves from a primitivism to a Surrealism, to a drip-style of Abstract Expressionism all within about 10 years, which is quite phenomenal growth.”

Snyder says he is particularly inspired by her earliest figurative works, which wrestle with cosmic questions of good and evil, war and peace. “These images are particularly poignant given the war in Ukraine,” Snyder said. “Sobel’s work dealt with subjects of wartime and evil and childhood fear of a violent world, which she herself experienced. She touches on these feelings in such a powerful way that feel alive in our moment and time.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

:strip_icc()/BHG_PTSN19720-33d9cd22f6ab49e6a21982e451321898.jpg)

More Stories

Fresh and Airy Interior Design Living Room Ideas for Summer

Where Art and Sound Converge: Exploring Fine Art Photography and Music Artist Portraiture

Cooking Chinese Cuisine with Ease Using Jackery Solar Generator 5000 Plus